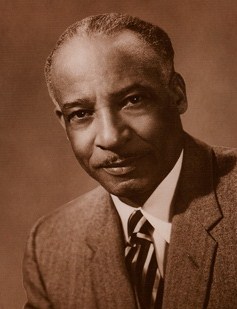

Adolphus Hailstork

Born in Rochester in 1941, Adolphus Hailstork spent most of his youth in Albany where he began singing and learning to play the violin, the piano, and the organ at an early age. His joining the choir of the Episcopalian Cathedral was an important milestone and a source of inspiration for a life-long interest in writing vocal music. He discovered his talent for composition through improvising at the piano, and he became active as a composer in high school – his early pieces being performed by the school choir.

He continued his studies at Howard University (B.M. in Theory), Manhattan School of Music (B.M. in Composition), and later on at Michigan State University (Ph. D.) under the tutelage of H. Owen Reed. He also spent the summer of 1963 at the American Institute in Fontainebleau, France, studying under renowned professor Nadia Boulanger. After graduating from Michigan State, he held positions at various colleges and universities. He is currently serving as Professor of Music and Eminent Scholar at Old Dominion University in Norfolk. He was awarded a Fulbright Fellowship in 1987, and named Cultural Laureate of the Commonwealth of Virginia in 1992. His compositional catalog encompasses a vast number of pieces in different genres and forms, and his music has been performed all over the country and beyond.

In 1974, Hailstork was commissioned by the J. C. Penney Foundation to write Celebration in preparation for the 1976 bicentennial festivities. The composition was played for the first time at the Black Music Symposium in Minneapolis in 1975, with Paul Freeman conducting. The piece was an instant success, and shortly thereafter it was recorded by the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. The work is in the form of a symphonic fanfare, with engaging rhythms in the irregular meter of 7/8 throughout most of the composition.

William Levi Dawson

We will follow this exciting introduction with the music of another American giant of the twentieth-century – William Levi Dawson (1899-1990). By all accounts, Dawson was one of the most influential African-American composers and educators of the last century.

Although known to many as an arranger of traditional spirituals, Dawson’s overall influence on American music and African-African musicians was monumental. From humble beginnings in Anniston, Alabama, Dawson left town at age 13 to study at the famed Tuskegee Institute. He had met musicians who were educated there and Dawson decided that studying at the venerable institution was the best course of action in the pursuit of his musical ambitions. He learned to play the trombone and the piano, took harmony lessons, and penned his first compositions by age 16. Booker T. Washington took him under his wings and made sure the young talented musician would see his educational journey challenge through. In 1921, at age 21, Dawson graduated with top honors from Tuskegee. He furthered his studies at the Horner Institute of Fine Arts (B. M.), the Chicago Musical College, and later on received his master’s degree from the American Conservatory in Chicago.

Dawson then embarked on a musical career that would span decades, starting with teaching school in Kansas from 1922 to 1926, and then becoming first trombonist with the Chicago Civic Orchestra (1926-1930). He was hired by the Tuskegee Institute in 1931 and began a 25-year collaboration with the institution – a partnership which has become legendary. Dawson led the famous Tuskegee Choir through national tours, wrote and arranged music for them, and in so doing he inspired a new generation of African-American musicians.

In 1934, Dawson was able to show one of his recent works, the Negro Folk Symphony from 1931, to the great conductor Leopold Stokowski. The famous Maestro was impressed with the piece, made a few suggestions, and then conducted the symphony with the Philadelphia Orchestra to popular and critical acclaim. The concert was also broadcasted adding to the success of this performance. Dawson’s reputation was cemented from then on.

The composer provided program notes to the premiere performance:

“This Symphony is based entirely upon Negro folk-music. The themes are taken from what are primarily known as Negro spirituals, and the practiced ear will recognize the recurrence of characteristic themes throughout the composition. This folk music springs spontaneously from the life of the Negro people as freely today [1934] as at any time in the past, though the modes and forms of the present day are sometimes vastly different from older creations. In this composition the composer has employed three themes taken from typical melodies over which he has brooded since childhood, having learned them at his mother’s knee.”

Yet this symphony had only begun its journey. Revisions were to take place decades later as Dawson became even more interested in African source materials. In 1952, he travelled to West Africa and visited seven countries so he could garner new musical inspiration from the field. Upon his return, he re-worked the Symphony into the form in which it is known today. Dawson thought that original African musical elements had been lost since slaves were brought to America, and the purpose of his trip was to re-discover some of these idioms and rhythms.

The first movement, The Bond of Africa, begins Adagio and features a main theme first introduced by the solo French horn. This theme later becomes a sort of leitmotiv or recurrent melodic line throughout the symphony. An Allegro section ensues, also beginning with a new theme played by the French horn, this time more rhythmic and syncopated in nature. The movement continues, halted in a dramatic fashion by the trombones with an unexpected Adagio, announcing the development. As the movement concludes, various rhythmic novelties are introduced, re-invigorating the texture as the opening themes are brought back.

The second movement, Hope in the Night, is more in the style of a spiritual. It begins Andante with a mournful English horn solo reminiscent of the opening theme. A contrasting Allegretto section breaks the calm and solemn character of the opening. The influence of Dvořák and of his New Worl Symphony are on display here. The movement closes with the opening theme, re-introduced by the English horn.

The last movement, O Le’ Me Shine, Shine Like A Morning Star!, begins as an Allegro con brio and remains as such throughout the movement. Here, perhaps than in the two previous movements, different rhythmic combinations are explored and more meters are displaced. Dawson’s rhythmic experiments stemming from his African musical findings truly shine, and this great symphony is brought to a rousing end.

The second half of our program will begin with a unique piece in a format never performed by TSO – a concerto for orchestra and solo string quartet.

With its two treble instruments (violins), its middle-register instrument (viola), and bass (cello), the string quartet is in itself a little symphony of four, benefitting from a wide array of available pitches and harmonic combinations, thus allowing composers to express the most sophisticated musical thoughts. It rose to pre-eminence in the Classical era (1750-1825) and became one of the most sought-after chamber music combinations thereafter. The string quartet usually performs as an independent unit, but there are a few instances where the ensemble is featured in a concerto setting – Elgar’s Introduction and Allegro being perhaps the most famous example.

The piece performed tonight, West Side Story Concerto for String Quartet and Orchestra, was arranged by American contemporary composer, arranger, and conductor Randall Craig Fleischer. It is comprised of ten short movements inspired by some of the main melodies from the famous 1957 Broadway musical.

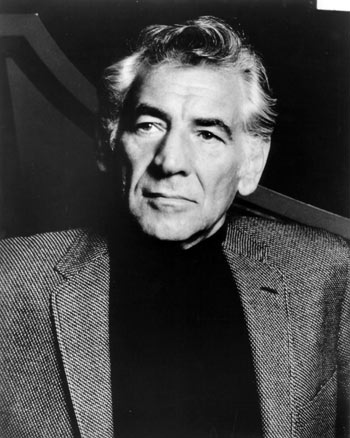

Leonard Bernstein

The original music was composed by another master of modern American music: Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990). Born in Boston to parents of Ukrainian-Jewish descent, he was captivated by the piano at an early age and soon started taking lessons. His father wanted him to become a lawyer but Leonard persisted with his desire to become a musician. He studied composition with Walter Piston at Harvard and conducting with Fritz Reiner at the Curtis Institute. His talents as pianist, conductor, and composer were soon recognized and his professional musical career took off in the 1940’s. In 1951, he became the head of orchestral and conducting departments at Tanglewood and music director for the New York Philharmonic in 1957.

Bernstein was a versatile composer, tapping every musical technique from tonal to serial, with a constant desire to reach out to the masses. West Side Story with lyrics by Stephen Sondheim turned out to be his masterpiece from that perspective. The story loosely based on Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet depicted the rivalry between two New York gangs and the love story between Tony & Maria, both associated with the different clans. The piece announced a new era in musical theatre as the tragic ending and themes of social injustice and race relations were brought forth.

Musically, the composer used the enigmatic interval of the tritone to convey the unsettling character of the story. He also mixed jazz idioms with Latin rhythmic and melodic materials – a new contribution to American music at that time and a somewhat prophetic concept in regards to the direction that American music would take later in the century. The concerto performed tonight will feature music from Mambo, Cha Cha, Maria, Tonight, and America, interspersed with more rhapsodic episodes (cadenzas) inspired from the original music.

And now for the big Finale – the winning piece of our first Audience Choice Award (drum roll): Main Title from Star Wars!

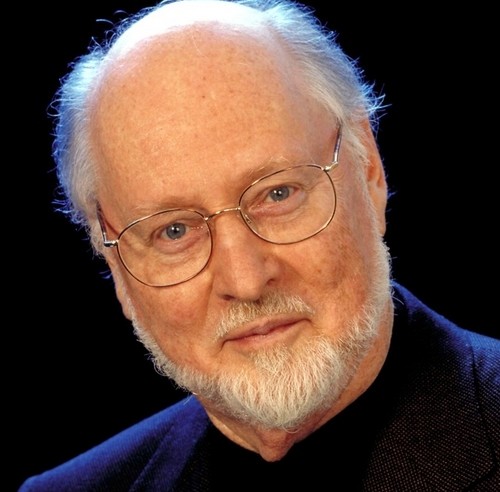

John Williams

Primarily known as a film-music composer, John Williams (b. 1932) is now regarded as one the greatest musicians of our generation. The son of a professional Jazz drummer, Williams first studied composition privately with Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco at UCLA. Following his service in the Air Force, he moved to New York City and trained as a pianist at the Juilliard School of Music under Rosina Lhévinne. After his studies he moved back to Los Angeles and worked as an orchestrator and studio pianist.

His popular breakthrough as a composer came in the 1970’s with scores to movies such as Jaws, Star Wars, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, and Superman. Today, at 83, Williams is still active as a composer and also conducts concert performances of his music, with the Boston Pops Orchestra among other orchestras, an ensemble with which he has been associated for a number of years. Williams is also a versatile composer whose music is not limited to the film-score style. He has produced a variety of classical pieces including a number of solo concertos and traditional vocal and orchestral compositions.

Main Title from Star Wars is probably one of Williams’ most famous themes. The music also begins with one of the most thrilling fanfares of the repertoire. The main theme, in march-style, is then introduced. It is followed by a series of short episodes introducing some of the musical elements that would be presented throughout the picture. The piece ends majestically.

The music to the Star Wars Series (begun in 1977) has become a model of great film scoring, and when it burst onto the scene, it announced a return to the grandiose and epic styles of earlier masters such as Max Steiner and Erich Korngold. Today, more than ever, this music speaks to a new generation of symphonic music lovers. It is truly a jewel in the crown of great American film scores.

©Marc-André Bougie, 2016