Tonight, TSO will reach two important milestones. We will first close our Beethoven symphony cycle with a performance of the composer’s Fourth Symphony. Then, we will perform our very first Mozart Piano Concerto. The Master’s 27 Piano Concertos – a musical canon as impressive as Beethoven’s 9 symphonies – represent a crowning achievement of the concerto genre and of the whole musical repertoire.

Wolgang Amadeus Mozart

Known in his early years as a musical prodigy and a master of keyboard playing, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) grew to become one of the greatest composers of all times. From his beginnings in Salzburg under the direction of his father Leopold – an accomplished musician in his own right – to studying and meeting with the some of the greatest musicians and pedagogues of the age (Padre Martini in Bologna, Johann Christian Bach in London, Joseph and Michael Haydn in Austria), Mozart was blessed with natural musical abilities and the perfect environment to foster such gifts. When Mozart left his native Salzburg in 1781 to settle in the musical capital of the world, Vienna, the young master was ready to take the world by storm and create even more music of timeless beauty. Sadly for us his work was cut short at the early age of 35 but the body of work he left behind – comprising well over 600 compositions – was a testament to the musical genius of a giant among giants.

In April of 1786, Mozart put the final touches to his comic opera Le nozze di Figaro (The Marriage of Figaro). The original 1784 story by French playwright Beaumarchais exposed the vices of contemporary nobility, a subject matter that then Austrian Emperor Joseph II wanted to avoid. Librettist Lorenzo da Ponte nevertheless convinced the monarch that he had re-worked the story as to not be offensive to good morals. Joseph II gave his blessing and the opera proved to be a monumental success. The Overture is the first piece of music heard at the beginning of the opera. The initial murmuring of the orchestra evokes the excitement building up as the characters set on a series of comical situations. The fanfare at the end of the Overture suggests the wedding celebration taking place in the last act of the opera. The Overture was written only two days before the premiere of the work on May 1, 1786. One of Mozart’s most easily recognizable compositions, it is a model of compositional perfection compactly set in sonata-allegro form. TSO began its musical history on April 4, 2006 with the performance of this piece as the first selection on the program.

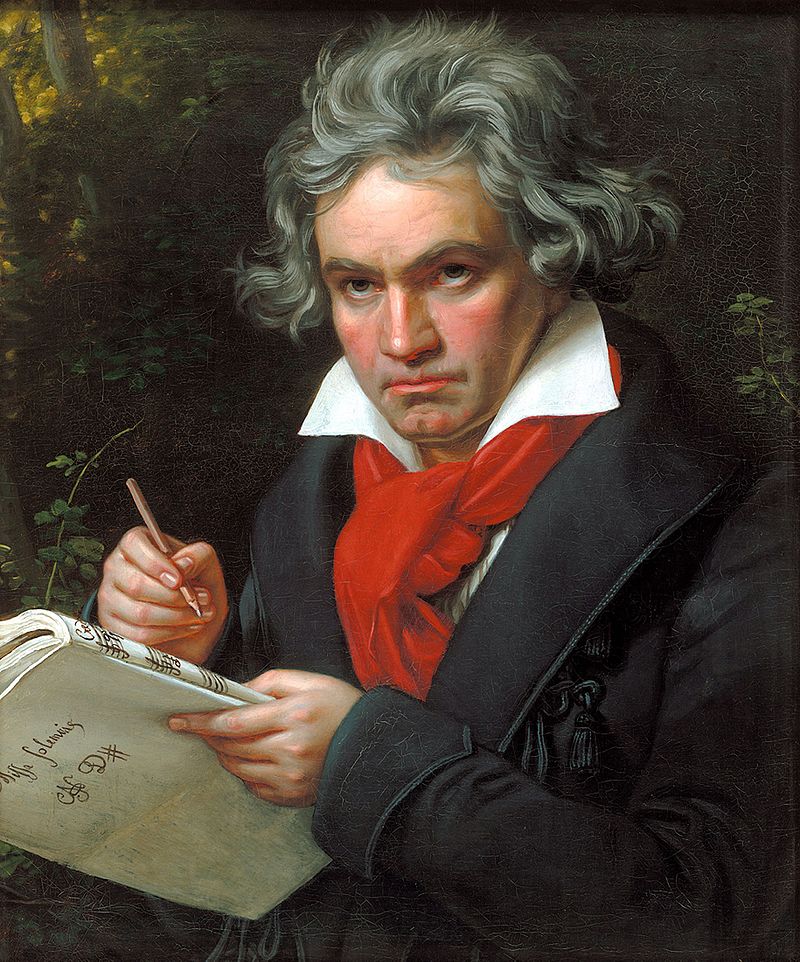

Ludwig von Beethoven

Born in Bonn, Germany, Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) lived through a difficult childhood to become one of music history’s greatest composers. Inspired by the earlier success of Leopold Mozart and his son Wolfgang, Beethoven’s abusive father wanted his talented son to be the next traveling prodigy. Unfortunately the young performer could not play well under pressure. Against all odds, Beethoven persisted in wanting to become a musician. He traveled to Vienna in the late 1780’s to study under Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809), and finally settled in the Austrian capital in 1792. Beethoven became a darling of the Viennese nobility, charming socialites with his impassioned piano playing style.

Towards the end of the 1790’s, signs of his impending deafness appeared. Beethoven became more introverted and avoided social contact. In 1802 he wrote the Heiligenstadt Testament, a series of letters addressed to his brother (but never mailed), and he came close to suicide. In the end, the master decided that he would not leave this world until he had written all the beautiful music still within him. This point usually marks the beginning of Beethoven’s second and most prolific period.

Above all, Beethoven is renowned as one of the greatest symphonists of all times, and each of his nine symphonies takes the listener through a unique and exhilarating journey. From his First, inspired by the teachings of Haydn, to the Third, the Fifth, and the Ninth which literally broke the mold of the genre, Beethoven evolved as a composer through his symphonic experiments. His even-numbered symphonies, often seen as stepping stones between his more well-known odd-numbered symphonies, are equally engaging and fascinating.

Beethoven wrote his Fourth Symphony in the summer and fall of 1806 while in Silesia visiting an admirer of his, Count Franz von Oppersdorff. The Count had been fascinated with Beethoven’s Second Symphony and he had convinced the Master to write another symphony for which he would have exclusive premiering rights. Beethoven agreed, halted his work on his Fifth Symphony, and completed the commission in a matter of weeks. The piece was then premiered in Vienna in March 1807 at the Lobkowitz Palace in Vienna. Oppersdorff was offended that Beethoven had broken their premiering agreement, and Beethoven sent a letter of apology. This was unfortunately characteristic of Beethoven who was always working to secure multiple sources of income to fund his career. His Fourth Piano Concerto and the Coriolan Overture were also premiered on the same program. The concert was successful and the new symphony was positively received and reviewed.

The Fourth stands apart in Beethoven’s symphonic output as the least performed of his symphonies, even though its musical quality is undeniable, and that it is at least equal to all of the other eight symphonies. To his contemporaries, the Fourth seemed as a reversal of the revolutionary advancements that the Master had instigated in his first three symphonies, and in retrospect, a total contrast to the impetus and dramatic intensity of the Fifth. But Beethoven’s inspiration followed its own pathway, and in the scheme of his total symphonic output, the Fourth stood as a beacon of Classical elegance and simplicity in a tumultuous sea of changes and innovations.

The first movement begins with a slow introduction, Adagio, in the parallel key of B-flat minor. Beethoven’s first two symphonies had slow introductions, but none as enigmatic and transparent as this one. It then moves through a series of modulations leading to the Allegro vivace. The movement evolves in the traditional sonata-allegro format, with the usual rhythmic intensity expected from a quick-paced symphonic movement by Beethoven.

The Adagio in E-Flat Major begins with a lyrical theme played by the first violins, and accompanied by a dotted-rhythm accompaniment figuration in the second. A beautiful second theme is then introduced by the solo clarinet. The movement reaches a climactic point when the first theme, high-lighted by a series of strong accents, is brought back in E-Flat minor. Beethoven brings the movement to a close in the original key.

The Allegro vivace, followed by the Trio (Un poco meno Allegro) is in the style of a Scherzo, even though it is not titled as such. The scherzo was Beethoven’s novel approach to the Classical Minuet and Trio format. Usually in ternary form (Minuet-Trio-Minuet), Beethoven repeats the Trio and Minuet at the end of the second Minuet, essentially turning this movement into a five-part structure.

The Allegro ma non troppo is a rollicking cascade of sixteenth-notes only temporarily interrupted to give way to a more lyrical second theme. Haydenesque in style, this movement clearly shows Beethoven’s perfect ease in writing music of incredible lightness and verve. If there is one rule for all of Beethoven’s symphonies, it is that none of them follow a similar path. The Fourth in its apparent simplicity and grace shows yet again another facet of the genius of the Master.

Mozart wrote his Piano Concerto no. 23 in Vienna in the winter of 1785 and 1786. During these months he was mostly preoccupied with putting the finishing touches to his opera Le nozze di Figaro, but he did find time to work on three new piano concertos (nos. 22, 23, and 24). Mozart’s reputation as a musician in Vienna had been established through his work as pianist, and especially through his composition and performance of piano concertos. Mozart was planning ahead and knew that such pieces would be needed later that year.

Mozart’s ability to work on multiple projects of different characters at the same time was phenomenal. Concertos no. 22 and 24, albeit totally different from each other, were in a class by themselves because of their scope and orchestration (use of trumpets and timpani). Concerto no. 23 was more intimate, and as such foreshadowed the style of Mozart in his later years.

The first movement, Allegro, features a double-exposition – a formal contribution that Mozart made to the genre of the concerto. The two main themes are first introduced by the orchestra, in the same key, and then re-introduced by the soloist, with accompaniment, following the usual path of modulations encountered in most contemporary compositions. The pianist then plays a contrasting third theme that leads into the development section. Towards the end of the movement, the pianist is featured in a solo cadenza. The orchestra closes the movement.

The second movement, Adagio, is perhaps Mozart’ most dramatic slow concerto movement. Set in the unusual key of F-Sharp minor, the solo piano introduces its introspective first theme, in siciliano rhythm, followed by a hauntingly beautiful orchestral response. A middle section in A major ensues, featuring a number of dialogues between the piano and woodwinds instruments. The opening music then returns, more contemplative than ever. The movement ends quietly, preceded by pizzicati in the strings and rich woodwinds colors. This is music from the heavenly realm. Few compositions in all of music have achieved this level of beauty and transcendence.

The final Allegro assai, introduced by the solo piano, brings us back to the colorful tonality of A major. Set in the form of a sonata-rondo, the movement evolves at break-neck with a series of figurations in eight-notes. The concerto ends gloriously as the soloist and the orchestra race to the finish line of this musical adventure.

©Marc-André Bougie, 2015