With this performance, TSO is reaching quite a milestone – the final concert of our tenth full season! Our first concert was presented on April 4, 2006 (a little over ten years ago), but our first full season officially began in September of 2006. It has been quite a ride since then! Our concert program was designed to link our past and our future, and we are grateful that you have chosen to celebrate this momentous event with us.

Clint Needham

We will begin the evening with a commissioned composition by none other than Texarkana-native Clint Needham (b. 1981). Texarkana has been a fertile ground for composers since the late 1800’s with celebrated creators such as Scott Joplin and Conlon Nancarrow. But musical composition is still alive and well in the Twin Cities and native son Clint Needham is putting us on the world map of music, once again. Please take the time to read Clint’s impressive biography included in this program book.

As for the commissioned composition, our request was that the piece be celebratory in nature, and in the style of a symphonic fanfare whose instrumentation would match that of Brahms’s First Symphony, the largest other anchor work on the program. Clint’s own words are perhaps better suited to explain his work:

“I wrote Flourish as both a celebratory piece for the Texarkana Symphony Orchestra as well as a work of gratitude for their patrons (all of you who are hear tonight). In recent years, I have seen many musical ensembles and arts organizations rise and fall quickly due to lack of support. The music presented here, while spirited, suggests the struggles that have been overcome in order for the Texarkana Symphony Orchestra to thrive. I am so impressed and grateful to this community for supporting the TSO and classical music.

Flourish was commissioned by the Texarkana Symphony Orchestra in celebration of their 10th year anniversary season. “

From all of us in Texarkana, Clint, Thank You for your magnificent work, and for the national and international spotlight that you shed on Texarkana through your professional endeavors.

We will continue our celebration with a performance of one of the most unique pieces of the concerto repertoire, from one of the favorite composers of TSO concert-goers, and featuring guest artists who have graced the Perot Theatre stage since the early days of our history.

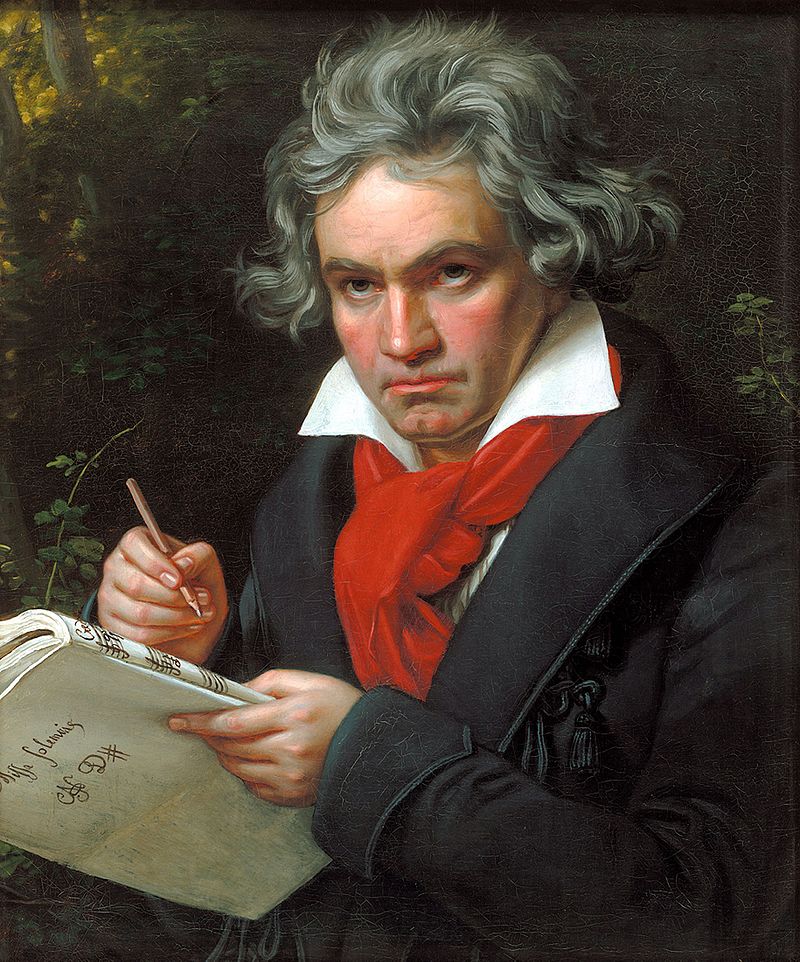

Ludwig von Beethoven

Born in Bonn, Germany, Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) lived through a difficult childhood to become one of music history’s greatest composers. Inspired by the earlier success of Leopold Mozart and his son Wolfgang, Beethoven’s abusive father wanted his talented son to be the next traveling prodigy. Unfortunately the young performer could not always do well under such pressure. Against all odds, Beethoven persisted in wanting to become a musician. He traveled to Vienna in the late 1780’s to study under Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809), and finally settled in the Austrian capital in 1792. Beethoven became a darling of the Viennese nobility, charming socialites with his impassioned piano playing style.

Towards the end of the 1790’s, signs of his impending deafness appeared. Beethoven became more introverted and avoided social contact. In 1802 he wrote the Heiligenstadt Testament, a series of letters addressed to his brother (but never mailed), and he came close to suicide. In the end, the Master decided that he would not leave this world until he had written all the beautiful music still within him. This point usually marks the beginning of Beethoven’s second and most prolific period.

Beethoven wrote the Triple Concerto for solo Violin, Cello and Piano during that second period. The piece was in the style of a Symphonie concertante, a genre similar to the concerto, but where a number of soloists were featured, in the manner of a Baroque concerto grosso. The concertante was especially popular in France, and Mozart and Haydn had composed a few pieces in that style in the years before. Yet, Beethoven’s unique combination of the solo violin, cello, and piano was a first, and the composition brought about several challenges, primarily making sure that each part would get equal treatment and receive the same attention. It was, in essence, a concerto for piano trio and orchestra. Fortunately, Beethoven had had experience writing for this particular chamber music combination.

We know that the Triple Concerto was composed between 1803 and 1804, but we are not quite sure for what reasons. Beethoven was teaching the Archduke Rudolf of Austria at that time – a young 15 years-old pianist with some talent – and it is believed that he might have composed the piano part with this performer in mind. However, there are no indication of a performance of the piece at that time. The concerto was actually officially premiered in 1808, and dedicated to somebody else, the Prince Franz Joseph of Lobkowitz.

The first movement, Allegro, begins quietly with a march-like theme featuring dotted-rhythms. The orchestral exposition continues presenting the main themes of the movement with the strength and intensity that we have come to expect from Beethoven. The solo cello then introduced the second exposition of the movement, followed by the solo violin, and then the piano. The movement continues with a development, recapitulation, and it is brought to a close with a rousing coda, Più allegro.

The second movement, Largo, is in the contrasting key of A-flat Major, and serves as a prelude to the third movement which is played attacca (without a break). Here again, the solo cello is introduced first, followed by the solo piano, and the solo violin. The movement features a beautiful main theme and a series of varied accompaniment figures.

The third movement, Rondo alla Polacca, is in the popular form of a rondo, a structure that Beethoven employed at many times for the last movement of large-scale pieces. The opening theme, or main refrain, is again introduced by the solo cello, followed by the violin, and then the piano. This rondo is said to be in the Polish manner, a style of music that was rather popular in aristocratic circles back in the early 1800’s in Vienna. The movement ensues according to rondo form, with episodes coming in-between the main refrain. The movement ends with an extensive coda, first featuring an Allegro in duple meter, before returning to the original meter, in tempo, right before the end. Beethoven’s experiment with this unusual format had come to a rousing end. No other composer have attempted writing a concerto for such a unique combination since.

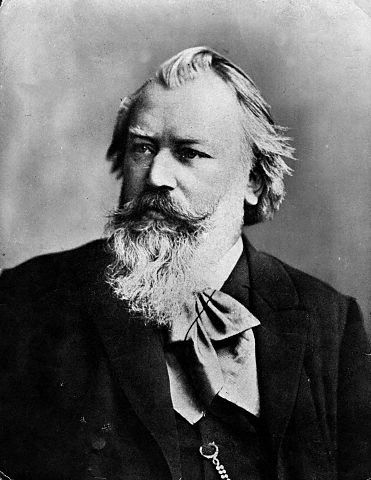

Johannes Brahms

The second half of our program will feature one of the most transformative compositions of the 19th-century – Johannes Brahms’s Symphony no. 1. Besides the historical significance of the piece, this composition also represents a milestone for our orchestra. After having explored the symphonic corpus of Beethoven for the last ten years, the time has come to introduce our audience to the great symphonic compositions that would follow. Brahms’ Symphony no. 1 is the door to that world.

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) was widely acknowledged as the most Classical of all Romantic composers. An admirer of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven, Brahms drew his compositional inspiration from these great masters. Though the music of Brahms is impassioned and Romantic in the musicological sense of the word, its structure is set in the Classical mold.

Born in Hamburg, Germany, Brahms showed signs of musical greatness early on, and his abilities at the piano and as a composer of solo pieces and vocal music were soon recognized. Robert Schumann brought Brahms to the fore in 1853 as he heralded the young composer as the bearer of the future of German music. Brahms was only 20 years old! Schumann suggested that the young composer explore the large forms of the concerto and the symphony, and that he took the mantle of becoming the rightful heir to the great German symphonic tradition of the earlier Masters. It was a tall order, to say the least.

It took the German master over forty years to find the courage to write a symphony after Beethoven’s nine masterful contributions to the canon. His four symphonies, less in number than any of his classical predecessors, are however majestic in conception and singularly original. The First, often nicknamed Beethoven’s Tenth, is Brahms glorious entry into the genre. The Second, more pastoral in nature, shows the tender side of Brahms’ musical personality. The Third, the shortest of the four, is perhaps the most passionate and thematically intricate. The Fourth is a cathedral of sound paving the way to Bruckner’s masterful creations.

Brahms worked diligently on different symphonic sketches, most of which became different pieces of music (for example, his first attempts at writing a Symphony in D minor was transformed into his first Piano Concerto). Brahms felt the weight of tradition and expectation at every turn, and he wanted all of his new compositions to be optimal. The work on the first symphony began in the 1850’s. In the meantime, he composed his two orchestral Serenades (1857-1859), the German Requiem (1869), and the Variations on a Theme by Haydn (1873). By then, in his early forties, he was ready to bring the final touches to his first symphony. The piece was finished in the summer 1876 at the Isle of Rügen, and it was premiered that year.

The first movement begins with a slow introduction, Un poco sostenuto, characterized by the pounding of the timpani, and ever ascending chromatic lines in the strings, and a contrasting figuration in the woodwinds. This is music of the utmost intensity: this first symphony was worth the wait after all! It is followed by an Allegro of a rare strength. It is set in the traditional format of sonata-form, and stays pretty close to tradition, with the exception of more modern modulations to foreign keys. The Allegro part of this symphony came from one of the earliest sketches of the piece. The slow introduction was added later on. Note the slow-building but powerful climax right before the recapitulation (about eight minutes into the movement). This is one of the great moments of Western music. References to Beethoven’s Symphony no. 5 are also obvious with a rhythmic motive resembling the opening notes of the famous symphony (short-short-short-long).

The second movement and third movement are unique in the sense that they are short in comparison to the outer movements. The Andante Sostenuto is a beautiful slow movement, imbued with the thick symphonic texture that Brahms had mastered by then. The lyrical first theme is contrasted by a more rhythmically driven second theme, accompanied by syncopated accompaniment figures. Brahms was a master of metric displacement and this stylistic attribute of his is obvious here. The movement ends peacefully, in the manner it began, and features a beautiful solo for violin and French horn.

The third movement, Un poco allegretto e grazioso, is neither a Menuet and Trio, or a Scherzo and Trio, but rather a typical Brahmsian Intermezzo with a contrasting middle section. It begins with a pastoral theme introduced by the solo clarinet, and is followed by a countersubject with descending scales in dotted-rhythms introduced a few bars later by the rest of the woodwinds family. A second theme, this time more rhythmic, is then introduced by the clarinet again. The middle section, in 6/8 meter, provides a Trio section contrast of sort to the opening music. It is followed by the return of the opening music, in the original duple meter.

Brahms had intended his first symphony to be end-weighted, and he did not disappoint with this last movement. Being a student of history, Brahms was aware of Beethoven’s predilection for longer last movements and extended codas, a Romantic musical feature that had become the norm by then. Yet, writing a consequential last movement after three opening movements was a challenge that not many composers could handle successfully. In here probably lies the reason why Brahms consciously chose to write shorter and lighter second and third movements as to leave room for the magnitude of this Finale.

It begins with a slow introduction, Adagio, hauntingly introducing the main theme of the movement, in a minor key and very slowly. The solemn character of the opening is interrupted by strings playing pizzicato (plucked strings), and giving impetus to the forward-going direction of the music. The sun finally shines through with the Più Andante, now in C Major, and featuring a gorgeous melodic line played by the solo French horn (inspired by an Alphorn melody that Brahms had heard years before). The trombones are also introduced shortly thereafter for the first time in the piece in a solemn chorale section. The main theme of the movement is then introduced, Allegro non troppo, ma con brio. It is first played by the strings and horns, and shows a clear resemblance to the Ode to Joy theme from Beethoven’s Symphony no. 9. Brahms was aware of the comparison and saw this music as an homage to the Master. The movement builds in intensity as it reaches its coda, Più Allegro, bringing this symphony to a monumental close. The challenge of following in Beethoven’s footsteps had been met, and Brahms had established himself as the rightful heir to the great German symphonic tradition.

The Symphony was premiered on November 4, 1876, in Karlsruhe, then in the Grand Duchy of Baden. Felix Otto Dessoff conducted. The reputation of the piece was cemented when, in 1877, the famous conductor Hans von Bulöw referred to the symphony as Beethoven’s Tenth.

© Marc-André Bougie, 2016