We are thrilled that you have decided to join TSO for a fiery symphonic ride on the opening concert of its 10th season. What a milestone! Tonight, we will bring you some of the most brilliant and colorful music of the orchestral repertoire. Russian composers have made a monumental contribution to the symphonic canon of the last two centuries and this concert will offer an outstanding sampler of these musical riches.

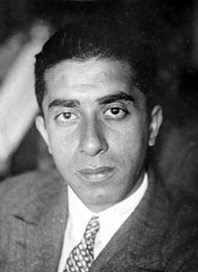

Aram Khachaturian

The evening will begin with music from a composer of the Soviet era of Russian history. Aram Khachaturian (1903-1978) was born in Georgia, a region which later became part of the Soviet Empire. Although Khachaturian was of Armenian heritage, he embraced the changes following the 1917 revolution and played an important role in the development of Soviet music during the twentieth-century. The Soviet Federation had become a cosmopolitan entity and the political elite wanted the country’s music to reflect the diversity of its many ethnic groups. Khachaturian’s music clearly contributed to this diversity. He was mostly in good terms with the political establishment of his country safe a short fall in favor following the Second World War. His music was accessible, popular, and of great quality – elements that were in line with socialist artistic ideals. Later in life he travelled the world conducting his works and promoting Russian music and composers.

Outside of the Soviet sphere of influence, Khachaturian’s compositions were some of the most popular pieces of all Russian music of the 20th-century. The opening selection of this concert in particular – the Sabre Dance – was a major symphonic blockbuster of the last century, and became a major hit in America in the late 1940’s. It was excerpted from the Ballet Gayane which the composer wrote in 1942. The story of the ballet is that of young Gayane, a collective farm worker whose husband is a smuggler and all-around petty criminal. Gayane denounces him to the local authorities and she finally marries the head of the local militia responsible for keeping order in the collectivity. The Sabre Dance was originally entitled Dance of the Kurds as the music featured Kurdish folk musical elements. Incidentally, the Sabre Dance was added to the ballet after it was completed. It did more to cement Khachaturian’s worldwide reputation than any of his other compositions. The music’s infectious rhythms, sparkling orchestration, and folk-like appeal have proven irresistible. From the opening xylophone solo to the middle section cello feature – itself a traditional Kurdish wedding melody – the short number oozes excitement and verve.

Khachaturian himself would be happy to know that we elected to present another composition of his this evening as to remind our audience that he wrote other pieces besides the Sabre Dance! The Masquerade Suite was put together in 1941 following the composer’s incidental music to the eponymous play by 19th-century Russian playwright Mikhail Lermontov. The play – loosely based on Shakespeare’s Othello – tells of an aristocrat who, suspecting his wife of adultery, poisons her, later to find out that she was innocent.

The opening Waltz, ardent and passionate, is probably the most famous number of the whole suite. Khachaturian’s gift for melody is apparent here as well. It is in ABA format and offers a contrasting and luminous middle section. The Nocturne, a type of night music as the evocative title suggests, sets a peaceful atmosphere enhanced by the warm sounds of the solo violin. The contrasting Mazurka resumes the spirit of dance with its engaging rhythmic and dynamic contrasts. Like the opening Waltz, this number is in ABA structure. The Romance, with its warm string section, clarinet, oboe, and trumpet solos provides a last introspective respite, comparable to that of the Nocturne. The Suite ends triumphantly with a tempestuous Galop at break-neck speed.

Pyotr Illyich Tchaikovsky

His personal life was difficult and he suffered severe bouts of depression throughout his life. Tchaikovsky married unhappily in 1877 and separated shortly thereafter. In the same year, he began a correspondence with a wealthy patron named Najeda von Meck who supported him financially to such an extent that he was able to commit himself entirely to composing for the next thirteen years. The two never met but maintained a strong relationship through their letters. Tchaikovsky died from cholera in 1893 after drinking un-boiled water, only nine days after the premiere of his Sixth Symphony. Many have speculated that he may have done so purposely.

In 1880, Tchaikovsky was approached by his mentor Nikolay Rubinstein to compose a piece of celebratory music for a number of high-profile events coming up in the near future – not the least being the completion of the Cathedral of Christ the Savior in Moscow to commemorate the 1812 Russian victory against Napoleon’s army. Tchaikovsky was not especially interested in writing such music to order but nevertheless began work on the composition.

The 1812 Festival Overture was set in the form of a symphonic poem rather than as an opening to anything else as the title might suggest. Overtures had evolved considerably since the days of the Baroque and Classical eras when such compositions were meant to precede larger works such as operas, oratorios, or instrumental suites. Tchaikovsky structured the composition as a pretty straight-forward description of the events leading up to the Russian victory, beginning with the cello and viola sections playing the Eastern Orthodox hymn “God Preserve Thy People”. It is followed by a massive and dynamic section featuring a number of contrasting musical themes (the first one being introduced by the solo oboe) – the said musical section being a representation of the brewing conflict and upcoming confrontation. Echoes of the French Marseillaise are heard announcing the impending arrival of the French troupes. This thematic development ensues with ever-stronger off-beats accents giving constant impetus to the music. The historical of Battle of Borodino between the French and Russian is on! As the French army retreats, an extended decrescendo featuring canon shots follows. The opening hymn “God Preserve thy People” is then heard again, accompanied by the toiling of church bells to announce this momentous event. It is followed by another hymn, this time “God Save the Tsar”, accompanied by more canon shots. To say that the piece ends triumphantly would be an understatement.

This unique composition presents performance challenges that have been met in different ways throughout history. Securing canons for a live performance is difficult, and it would be even more challenging to musically coordinate their sounds with that of the rest of the orchestra (not to mention getting a permit from the Fire Marshall to perform such a feat indoors!). The toiling of church bells is also problematic unless the piece is performed in a church or outdoors, close to a church. Tchaikovsky also calls for a limitless number of brass instruments (Banda) to join in the final segment of the piece. Nonetheless, adjustments have been made so that this quintessential celebratory masterpiece may be enjoyed for generations.

The piece, although it contributed in making Tchaikovsky internationally famous, was never performed exactly as intended when the composer was alive. It was premiered indoors, with conventional orchestration, at the Arts and Industry Exhibition in 1882. The Cathedral was completed in 1883.

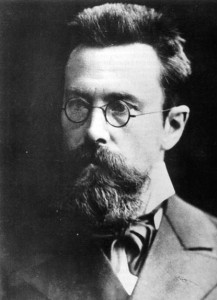

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

Unlike many other European musical traditions, Russian music only really came of age in the 19th-century, or what is commonly known as the Romantic era in music. During previous centuries, Russian royalty and aristocrats imported trained musicians from Europe to fulfill their musical needs. A young musician named Mikhail Glinka (1804-1857) changed this trend in the early 1800’s and established a Russian Classical music tradition. Nationalism was growing all over Europe, including Russia. Then a group of composers nicknamed The Russian Five (or The Mighty Handful), including Balakirev, Borodin, Cui, Mussorgsky, and Rimsky-Korsakov followed, firmly establishing this new Russian musical tradition.

Many of them were musical amateurs and pursued other professional goals, including Rimksy-Korsakov who began his musical career as a well-trained amateur, working as a naval officer and composing music in his spare time. During that time he travelled all over the world and became acquainted with the music, sounds, and colors of different locales. These experiences had an undeniable impact on his musical imagination, especially as it pertained to his treatment of instrumental timbre.

Capriccio espagnol is one of these pieces that set Rimsky-Korsakov apart as a master of the art of orchestration. Originally conceived as a fantasy on Spanish themes for solo violin and orchestra, it evolved towards its modern form as the composer worked through the details of the composition. The piece retained rhapsodic elements of the original concept – through a number of solos and features for not only the violin, but also woodwinds and brass instruments, as well as the harp. The interest of the piece lies in the highly effective orchestral treatment of each section of the suite. Rimsky-Korsakov achieves musical interest not through thematic or harmonic development but rather through coloristic expansion. The composer often frowned upon the fact that many commented on this composition being well orchestrated. For Rimsky-Korsakov, thinking through orchestral color was the compositional process. Unlike many composers, he did not write his music at the piano first: he composed directly for the instruments available to him through the orchestral palette.

The suite begins with I. Alborada, an aubade (or dawn music) usually played by shepherds at daybreak and accompanied by a bagpipe or light percussion instrument. It is traditional music from the north of Spain. Rimsky-Korsakov’s treatment of the music is bright and invigorating. Notice the oboe and violin solos. It leads into II. Variazoni, a set of variations featuring the French horns at first. Here again, the genius of the composer is in constantly refreshing the timbral texture. Notice also the English horn and flute solos. Next the III. Alborada is brought back, in a different key and with changes in orchestration. Notice the clarinet solo towards the end. It is somewhat of a musical sorbet before IV. Scena e canto Gitano (Scene and Gypsy song). This movement is a series of solo cadenzas or moments of virtuosity. It begins with the French horns and is then followed with the solo violin, flute, clarinet, and harp. Percussion instruments provide accompaniment textures to these features. A spirited dance section in triple time follows, leading directly into V. Fandango asturiano, an energetic dance from the north of Spain. This movement is the coloristic climax of the composition – and perhaps of all music composed up to this point in music history. The theme of the Alborada is brought back in the end.

Rimsky-Korsakov composed Capriccio espanol in 1887, and it was premiered on November 12, the same year, in St. Petersburg. The piece was an instant success with the public and within musical circles. Orchestra musicians were especially impressed the Master’s genius for extracting such beauty and new and exciting sounds out of the orchestra. The amateur Russian naval officer had taught a lesson in musical colors and beauty to the whole world!

Igor Stravinsky

Stravinsky was born in Oranienbaum, Russia, into a musical family. His father was a bass singer at the Imperial Opera in St. Petersburg and his mother an accomplished amateur musician in her own right. He met many of the Russian Five early in his musical training and this had a fundamental impact on his musical development. Rimsky-Korsakov became his teacher and the young Igor made steady progress under the tutelage of the older Master. Early on, Stravinsky’s music displayed the hallmarks of his style – a rhythmic drive and intensity of the highest order. This was already apparent in Fireworks, one of his first symphonic works composed in 1908. His work on the Firebird ballet in collaboration with the impresario Sergei Diaghilev would be his first major success – an event that put him on the musical map of the world. His next two ballets, Petrushka and The Rite of Spring, also written in collaboration with Diaghilev, would have a considerable impact on the history of music, the latter being perhaps the most influential piece of music in the 20th-century. Stravinsky kept a busy schedule for the rest of his career, including conducting his own work. He finally settled in America in 1939 and became a naturalized citizen in 1945. His professional endeavors were lucrative and Stravinsky remained successful and active until he died of heart failure at 88, in 1971.

Stravinsky was only 27 when he was approached by Diaghilev to write the music to the Firebird. Diaghilev had approached other composers, with mixed results, and he thought that the young Russian composer might be able to step up to the plate. The audacious impresario wanted to expose the Parisian public to the atmosphere of folk Russia, a concept he thought would appeal to the ever-curious Parisian public. By the time Stravinsky received the official request to start working on the piece, he had already got echoes of this possibility and had begun work on it. The production and collaborative work with Diaghilev and choreographer Michel Fokine ensued and the final production was ready for performance in Paris on June 25, 1910. The rest – as they say – was history. The production was an immense popular and critical success and Stravinsky’s career was launched. Diaghilev’s gamble had worked.

The story of the Firebird is that of a hunter, Prince Ivan, chasing a wonderful bird with feathers of fire – the Firebird. Pleading for her life, the Firebird offers Ivan one of her feather, giving him the power to magically call upon her in a period of great need. As Ivan pursues his journey, he falls in love with a beautiful young maiden living within the realm of eternal evil figure, King Kastchei. Ivan enters the King’s castle and confronts him. He conjures the help of the Firebird through the magic feather, and Kastchei and his minions dance themselves to madness. Ivan learns that the secret to Kasthchei’s immortality lies in his soul being kept in a secret egg. Ivan finds the egg, destroys it, and the evil king dies. The Kingdom and its subjects are free at last, and Ivan can marry his Princess.

In the beginning of Introduction, music referencing the evil King is played, setting an ominous mood. Unusual effects in the string section are used to create a gloomy atmosphere worthy of the dark realm of Kastchei. It leads directly into L’oiseau de feu et sa danse (The Firebird and her Dance), a musical depiction of the Firebird and of Hunter Ivan’s quest for it. A series of variations ensues. Ronde des princesses (Round of Princesses) depicts the fairy-like world of the maidens Ivan encounters on the outskirts of the King’s castle. The music employs simple Russian folk melodies. The Danse infernale du roi Kastcheï (Infernal Dance of King Kastchei) accompanies the King and his company falling under the spell of the Firebird in a mad dance. This is perhaps the most famous section of the Suite. The Berceuse (Lullaby), featuring the solo bassoon, follows as the King and his minions reach exhaustion. The music leads directly in the Final (Finale), a glorious conclusion to this incredible journey. Simple Russian melodies are used as primary thematic materials, enhanced through ever brilliant orchestration. This is truly a great moment in the history of music. Rimsky-Korsakov would have been proud of his student!

The version performed tonight was arranged by Stravinsky in 1919. It features a smaller instrumentation than that of the original version which was, by all means, immense (quadruple woodwinds, three harps, etc.). The 1919 version is the most popular of the three versions of the work made by the composer himself (1910, 1919, and 1945 versions).

©Marc-André Bougie, 2015